Introduction

The development of the silicon neuromorphic cochlea, referred to as the Dynamic Audio Sensor (DAS), by researchers at the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich, represents a profound departure from conventional digital signal processing (DSP). This technology is not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental shift in computational philosophy, rooted in the principles of biological neural systems. By emulating the hydro-mechanical and electro-chemical processes of the human inner ear, the neuromorphic cochlea processes sound in a parallel, asynchronous, and event-driven manner. This architecture allows it to achieve orders of magnitude improvements in energy efficiency and latency compared to traditional, frame-based audio processors. The device’s ability to compress raw sensory data into a sparse stream of “spikes” and its compatibility with other neuromorphic sensors position it as a cornerstone for future applications in edge computing, hearing aids, and autonomous robotics. The work is led by the Sensors Group at the Institute of Neuroinformatics, a unique collaboration between the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich, demonstrating the power of interdisciplinary research to bridge the gap between neuroscience and engineering.

1. A Foundational Shift in Auditory Computing

The landscape of modern computing is largely defined by the von Neumann architecture, a model in which a central processing unit (CPU) is physically separate from memory. While this design has driven technological progress for decades, it is inherently inefficient for processing the vast, continuous streams of data generated by real-world sensors, such as microphones and cameras. The constant movement of data between memory and the processor, known as the von Neumann bottleneck, leads to significant latency and high power consumption, particularly in applications that require real-time processing. For instance, a conventional audio system must continuously sample and digitize an analog signal, regardless of whether any meaningful sound is present. This process generates massive volumes of redundant data that must be buffered and processed, consuming excessive power and introducing unavoidable delays.

To address these limitations, the field of neuromorphic engineering has emerged as a discipline focused on building electronic systems that emulate the brain’s efficient computational style. This approach abandons the conventional reliance on sequential, high-precision digital hardware in favor of designs inspired by neurobiology. Neuromorphic systems are characterized by several core principles: massively parallel processing, event-driven computation, and the co-location of memory and processing. The origins of this field can be traced back to the late 1980s, when pioneers like Carver Mead at Caltech began to explore treating transistors as analog devices rather than simple digital switches. Mead’s work on the first silicon retina and silicon cochlea laid the philosophical and technical foundation for the entire field of neuromorphic engineering, which has since been progressed by a new generation of researchers. Therefore, the work at the University of Zurich, while a globally significant leap forward, is the culmination of decades of sustained, diligent scientific effort rather than a singular, sudden breakthrough.

This fundamental re-conception of computing is not an incremental gain but a rejection of the wasteful, data-intensive model for sensory tasks. The core value of neuromorphic technology lies not just in the hardware but in a profound paradigm shift from a synchronous, data-driven model to an asynchronous, information-driven one.

|

Computational Model |

Conventional (von Neumann) |

Neuromorphic (Brain-Inspired) |

|---|---|---|

|

Architecture |

Separated memory and processing |

Co-located processing and memory |

|

Data Representation |

Dense frames of continuous data |

Sparse, asynchronous spikes/events |

|

Processing Style |

Sequential, synchronous |

Massively parallel, event-driven |

|

Power Consumption |

Constant, high (mW to W) |

Activity-dependent, ultra-low (µW) |

|

Latency |

Fixed, often high (ms) |

Dynamic, ultra-low (µs) |

2. The Biological Blueprint: How the Human Ear Informs Engineering

To appreciate the engineering genius of the silicon neuromorphic cochlea, one must first understand its biological inspiration. The human cochlea is a marvel of energy-efficient sensory processing, transforming physical sound waves into neural signals with minimal power expenditure. This fluid-filled, spiral-shaped structure, part of the inner ear, functions as a hydro-mechanical system. The incoming sound waves induce vibrations in the basilar membrane, a structure that runs the length of the cochlea. A crucial principle of its function is tonotopic mapping, where the physical properties of the basilar membrane cause it to resonate at different points for different sound frequencies. High-frequency sounds excite the basal (beginning) part of the cochlea, while low-frequency sounds excite the apical (end) part.

This mechanical energy is then transduced into electrical neural signals by inner hair cells, which are exquisitely sensitive to the vibrations of the basilar membrane. The brain’s auditory system does not receive a continuous, high-volume stream of raw audio data. Instead, the neurons of the auditory nerve encode this information into a sparse stream of “spikes” or “events,” which are transmitted asynchronously. This sparse, event-based encoding is the key to the brain’s unparalleled efficiency. Rather than processing all incoming data, the biological system only transmits information when a significant change or event occurs, a fundamental distinction from conventional digital processors that must constantly process every data point.

The challenge for neuromorphic engineers is not to improve upon a digital system, but to abandon that paradigm entirely and replicate the more efficient, analog, and parallel style of biological computation. The human cochlea’s efficiency, operating on the order of microwatts of power, stems directly from its analog-first, event-driven nature, which stands in direct contradiction to the sequential, data-intensive methods of conventional digital signal processors (DSPs).

3. The University of Zurich’s Contribution: The Dynamic Audio Sensor (EAR)

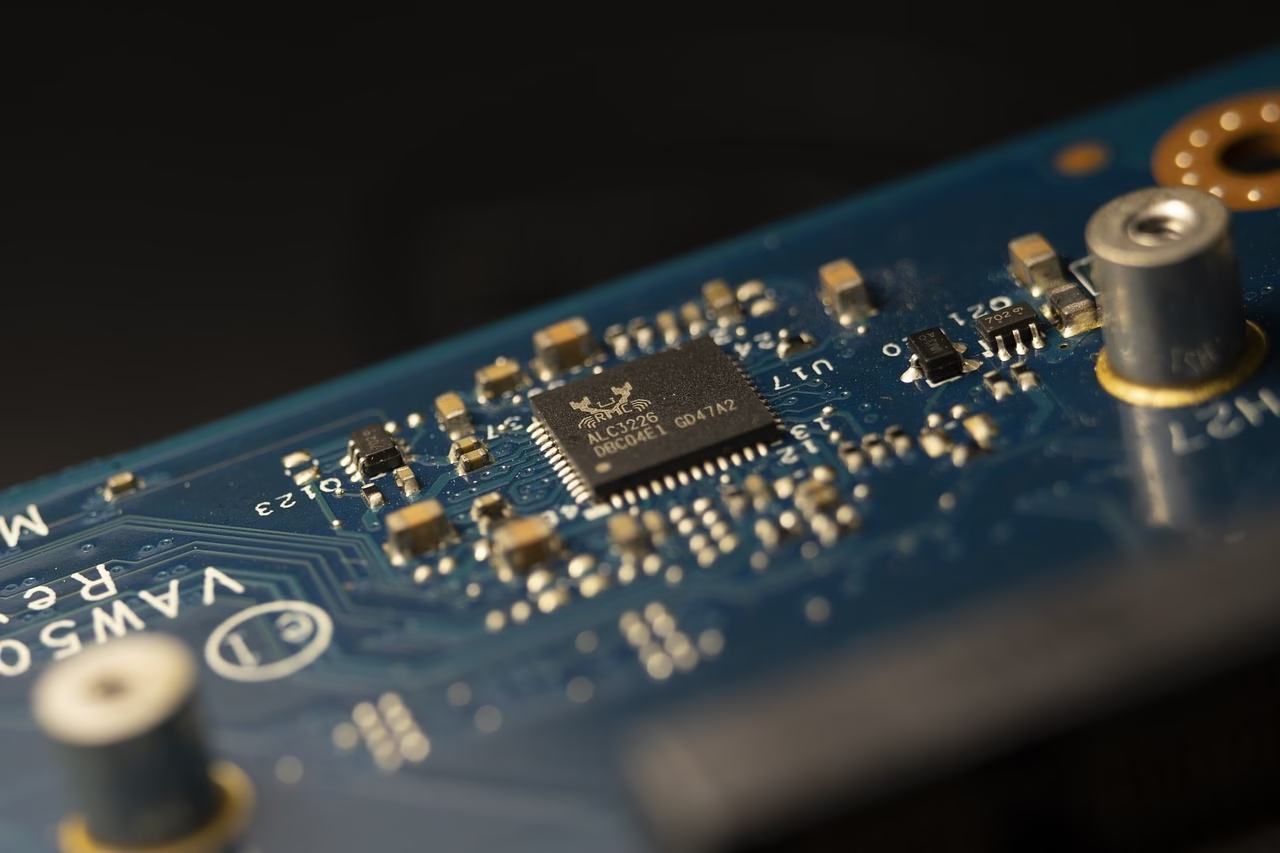

The University of Zurich’s pioneering work in neuromorphic engineering is encapsulated in a family of devices known collectively as the silicon cochlea or EAR, which has evolved through several generations, including the early AER-EAR , the AEREAR2 , and the more advanced Dynamic Audio Sensor (DAS1). These devices were developed at the Institute of Neuroinformatics (INI), a joint institute of the University of Zurich (UZH) and ETH Zurich. The core of these chips is their analog Very Large-Scale Integration (aVLSI) architecture, which physically emulates the biological circuits of the human ear.

The operational principle of the silicon cochlea can be understood as a three-stage process that directly mirrors the biological function:

- Stage 1: The Cascaded Filter Bank. The incoming audio signal is first fed into a series of cascaded second-order filters. This filter bank models the physical oscillation of the basilar membrane, with each stage tuned to a specific frequency. The researchers at INI chose a cascaded architecture over a parallel, coupled one for its superior robustness and better matching properties, which are critical for mitigating the effects of manufacturing variances. This architectural choice is a deliberate engineering decision that directly contributes to the device’s superior performance and reliability.

- Stage 2: The Inner Hair Cell Model. The output from each filter section is then processed by a half-wave rectifier circuit. This circuit emulates the function of the biological inner hair cells, which transduce the mechanical vibrations of the basilar membrane into an electrical signal. This analog pre-processing step is crucial because it inherently filters out silence and redundant data at a fundamental hardware level.

- Stage 3: The Ganglion Cell and Event Generation. The rectified electrical signal from each channel is then sent to a pulse frequency modulator (PFM) circuit, which models the behavior of auditory ganglion cells. These circuits generate a sparse, asynchronous stream of digital “spikes” or “address-events.” Each spike represents a specific event: a significant change in a particular frequency channel. This output is encoded using the Address-Event Representation (AER) protocol. The analog front-end acts as a gatekeeper, and only when a significant change in sound occurs does it generate a spike. This causal link is what leads to the immense power savings and efficiency seen in the system.

The Dynamic Audio Sensor (DAS1) is a binaural chip, containing two separate 64-stage cascaded filter banks, enabling it to process stereo audio inputs and extract spatial information. The chip also includes on-chip features like microphone preamplifiers and digitally controlled biases, and its output is designed to be easily processed by host software like jAER. The logarithmic spacing of the channels mimics the tonotopic arrangement of the biological cochlea, ensuring a faithful representation of the input.

4. The Neuromorphic Advantage: A Comparative Analysis

The silicon neuromorphic cochlea surpasses conventional audio processors not through incremental improvements but through a different computational philosophy. A traditional DSP, even a highly optimized one, operates by converting an analog signal to a digital representation via an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) and then processing it using algorithms like the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). This process is inherently wasteful as it processes every sample, including silent periods, and requires a continuous power supply. The neuromorphic cochlea, by contrast, operates on a “process-on-demand” model.

4.1 Comparative Metrics: Neuromorphic vs. DSP

- Energy Efficiency: The primary advantage of the neuromorphic cochlea is its unparalleled energy efficiency. Neuromorphic systems are event-driven, meaning that only the neurons and synapses actively processing an event consume power, while the rest of the network remains idle. This concept, known as “activity sparsity” , contrasts sharply with the continuous power draw of a conventional DSP’s clock and processing units. A comparative benchmark for a similar neuromorphic processor, the Xylo Audio 2, demonstrated a best-in-class dynamic inference power of 291 μW for a keyword-spotting task. This level of efficiency is critical for battery-powered devices in the Internet of Things (IoT) and wearable technology.

- Latency: The asynchronous, event-driven nature of the neuromorphic cochlea results in ultra-low latency, which is reduced to the analog delay along the filter bank. This is a fundamental advantage over DSPs, which are constrained by fixed-frame processing delays and sequential data movement. The temporal resolution of the neuromorphic cochlea can be on the order of microseconds, and an on-time localization algorithm running on the output has been shown to offer lower latency than conventional cross-correlation methods.

- Data Handling: The neuromorphic cochlea’s output naturally compresses the raw data stream. Instead of a continuous, high-volume flow of redundant audio frames, it generates a sparse stream of events that reports only changes. This drastically reduces the data bandwidth and processing load on subsequent stages, leading to a more efficient and scalable system.

4.2 Limitations and Trade-offs

Despite these advantages, the technology is not without its trade-offs. While analog hardware is more power-efficient, it can be susceptible to device mismatches during fabrication. The INI team mitigated this challenge by choosing a robust cascaded architecture and incorporating on-chip digitally controlled biases. A broader challenge for the field of neuromorphic computing is the lack of standardized benchmarks, making it difficult to perform fair comparisons between neuromorphic systems and conventional ones, as highlighted by initiatives like the NeuroBench project. The complexity of fully modeling biological neurons, as seen in the computationally demanding Hodgkin-Huxley model, also presents a theoretical and practical challenge for real-time systems.

|

Metric |

Neuromorphic Cochlea (e.g., DAS1) |

Conventional Audio Processor (DSP/MCU) |

|---|---|---|

|

Power Consumption |

18.4 mW – 26 mW (chip, dependent on activity) |

High (often hundreds of mW to W) |

|

Latency |

Reduced to analog delay (\pm 2 \text{ µs} jitter) |

Fixed frame delay (milliseconds) |

|

Processing Principle |

Event-driven, asynchronous |

Fixed-rate, synchronous |

|

Data Output Rate |

~20 keps (events per second, for speech) |

MB/s (large data stream) |

|

Dynamic Range |

Very high (spikes can be far or close) |

Limited (typically 90 dB) |

5. The Hub of Innovation: Research Groups at UZH and ETH Zurich

The success of the silicon neuromorphic cochlea is a direct result of the unique, interdisciplinary structure of its primary research hub: the Institute of Neuroinformatics (INI). This institute is a joint venture between the Faculty of Science at the University of Zurich and the Department of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering at ETH Zurich. This collaboration is not coincidental; it is a deliberate architectural choice that allows researchers to seamlessly merge knowledge from neuroscience and engineering, which is the foundational premise of neuromorphic design.

The primary research group responsible for the silicon cochlea and other neuromorphic sensors is the Sensors Group at INI. The key researchers who have led this work are Professor Shih-Chii Liu and Professor Tobi Delbruck. Their long-standing collaboration has been instrumental in the development of the AEREAR2 and the Dynamic Audio Sensor (DAS1), with numerous publications detailing their work. The researchers have been awarded for their work in low-latency, low-power sensors for speech detection.

It is important to distinguish this specific neuromorphic engineering work from other, distinct research areas at the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich. For instance, the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at UZH conducts clinical research on conventional cochlear implants, focusing on improving surgical outcomes and understanding the inflammatory response to implanted materials. Similarly, researchers at ETH Zurich have developed a smart earpiece for stroke recovery that uses electrical impulses to stimulate the vagus nerve, a project unrelated to the neuromorphic cochlea’s auditory processing function. This distinction is crucial for a nuanced understanding of the broader auditory research ecosystem at these institutions. The success of the neuromorphic cochlea is a direct consequence of the unique institutional structure that fosters a close working relationship between experts in neuroscience and electrical engineering.

|

Researcher Name |

Affiliation |

Research Group |

Key Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Prof. Shih-Chii Liu |

University of Zurich / ETH Zurich |

Sensors Group (INI) |

Key figure in the development of the AEREAR and Dynamic Audio Sensor (DAS1); leader in low-latency, low-power speech detection. |

|

Prof. Tobi Delbruck |

University of Zurich / ETH Zurich |

Sensors Group (INI) |

Pioneer in neuromorphic vision sensors (silicon retina) and a long-time collaborator on the silicon cochlea project. Co-organizes the Telluride Neuromorphic Engineering workshop. |

|

Alpha Renner, Raphaela Kreiser, Julien Martel |

University of Zurich / ETH Zurich |

Neuromorphic Cognitive Robots (NCR) Group (INI) |

Ph.D. students and collaborators working on neural architectures for autonomous robots, including neuromorphic SLAM and motor control. |

|

Dr. Adrian Dalbert, PD Dr. Jae Hoon Sim, Prof. Alexander Huber |

University of Zurich |

Department of Otorhinolaryngology |

Clinical research on conventional cochlear implants, including electrocochleography, bone conduction, and surgical techniques. Distinct from the neuromorphic device research. |

6. The Future Trajectory: Applications and Challenges

The neuromorphic silicon cochlea is not a stand-alone component; its greatest value lies in its potential to be integrated into a broader, interconnected neuromorphic ecosystem. Its event-based output, using the Address-Event Representation (AER) protocol, is compatible with other neuromorphic sensors like the dynamic vision sensor (silicon retina). This shared data format enables multimodal sensor fusion, a critical capability for advanced autonomous systems. A robot, for example, could combine sound and visual information to navigate or locate objects with greater robustness and accuracy, mirroring how the human brain integrates sensory inputs.

6.1 Current and Near-Term Applications

The profound advantages in power efficiency and latency make this technology ideal for a variety of applications where these metrics are paramount.

- IoT and Edge Computing: For always-on devices like smart speakers, remote sensors, and wearables, the neuromorphic cochlea’s ultra-low power consumption enables continuous listening for voice commands or ambient sounds with minimal battery drain. The event-driven processing allows for a sensor to “think for itself,” keeping the main application processor asleep until truly needed.

- Hearing Aids: By mimicking the brain’s ability to process sound, neuromorphic hearing aids could offer significant improvements over conventional devices by effectively filtering out background noise and enhancing speech clarity.

- Robotics and Autonomous Systems: The low latency and real-time processing are critical for robotic navigation. The neuromorphic cochlea can provide robust sound localization, which can be fused with data from neuromorphic vision sensors for more reliable environmental perception and object detection, even in noisy or visually challenging environments.

6.2 Enduring Challenges and Future Directions

The field of neuromorphic computing, while promising, still faces significant challenges. The lack of standardized benchmarks (e.g., NeuroBench) makes it difficult to conduct fair comparisons between competing neuromorphic platforms and against conventional technologies. Additionally, while the hardware is maturing, a full-stack ecosystem of software tools, algorithms, and training frameworks (e.g., for Spiking Neural Networks) is still required to fully exploit the hardware’s capabilities. This involves not only developing new algorithms but also fostering collaboration between computer scientists and neuroscientists to deepen the understanding of biological principles and their practical application.

7. Conclusion

The work on the neuromorphic silicon cochlea by the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich is a landmark achievement in a decades-long pursuit of brain-inspired computing. The technology is not merely a more efficient audio processor; it represents a fundamental paradigm shift away from the wasteful von Neumann architecture and towards a biologically inspired, event-driven model of computation. The device’s analog, cascaded architecture and its use of a sparse, asynchronous data representation grant it unparalleled advantages in energy efficiency, latency, and data handling. These attributes are not incremental gains but are the direct result of an intentional design philosophy that prioritizes efficiency and information over brute-force data processing.

The success of this work is a testament to the interdisciplinary collaboration at the Institute of Neuroinformatics, which has fused a deep understanding of neurobiology with advanced electronic engineering. The neuromorphic cochlea serves as a cornerstone for future generations of intelligent, energy-efficient devices, from consumer electronics and medical wearables to complex robotic systems. Its greatest potential lies in its integration with other neuromorphic sensors to create cohesive, multi-sensory systems that can perceive and interact with the world with an efficiency and adaptability previously confined to biological organisms. While challenges remain in benchmarking and software development, the foundation laid by these researchers marks a clear path toward a future where artificial intelligence and computing are inextricably linked with the profound insights of the human brain.

Works cited

1. Neuromorphic engineering: Artificial brains for artificial intelligence – PMC – PubMed Central, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11668493/ 2. Neuromorphic Computing. An overview of the history of… | by QuAIL Technologies – Medium, https://medium.com/quail-technologies/day-18-neuromorphic-computing-752e6020332d 3. A Review of Current Neuromorphic Approaches for Vision, Auditory, and Olfactory Sensors, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2016.00115/full 4. Why Sound Processing Takes Time, Not Just Frequency – EE Times Podcast, https://www.eetimes.com/podcasts/why-sound-processing-takes-time-not-just-frequency/ 5. Neuromorphic sensory systems, https://tilde.ini.uzh.ch/~tobi/wiki/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=liudelbruckcurropin10finalprintversion.pdf 6. Neuromorphic Engineering – CapoCaccia Workshops, https://capocaccia.cc/en/public/about/neuromorphic-engineering/ 7. What Is Neuromorphic Computing? – IBM, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/neuromorphic-computing 8. Neuromorphic Computing: Advancing Brain-Inspired Architectures for Efficient AI and Cognitive Applications – ScaleUp Lab Program, https://scaleuplab.gatech.edu/neuromorphic-computing-advancing-brain-inspired-architectures-for-efficient-ai-and-cognitive-applications/ 9. Carver Mead – Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carver_Mead 10. Large-scale neuromorphic computing systems – PubMed, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27529195/ 11. A Bio-Inspired Active Radio-Frequency Silicon Cochlea – ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224471992_A_Bio-Inspired_Active_Radio-Frequency_Silicon_Cochlea 12. Models of Cochlea Used in Cochlear Implant Research: A Review – PMC – PubMed Central, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10264527/ 13. Low-power devices could listen with a silicon cochlea – Embedded, https://www.embedded.com/low-power-devices-could-listen-with-a-silicon-cochlea/ 14. AER EAR: A Matched Silicon Cochlea Pair With Address Event Representation Interface, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/3451422_AER_EAR_A_Matched_Silicon_Cochlea_Pair_With_Address_Event_Representation_Interface 15. Neuromorphic Audio Systems – Meegle, https://www.meegle.com/en_us/topics/neuromorphic-engineering/neuromorphic-audio-systems 16. Early Auditory Based Recognition of Speech – SNSF Data Portal, https://data.snf.ch/grants/grant/126844 17. Real-time speaker identification using the AEREAR2 event-based silicon cochlea | Request PDF – ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261229029_Real-time_speaker_identification_using_the_AEREAR2_event-based_silicon_cochlea 18. Reconstruction of audio waveforms from spike trains of artificial cochlea models – Frontiers, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2015.00347/full 19. Reconstruction of audio waveforms from spike trains of artificial cochlea models – PubMed, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26528113/ 20. Dynamic Audio Sensor | iniLabs, https://inilabs.com/products/dynamic-audio-sensor/ 21. Sub-mW Neuromorphic SNN Audio Processing Applications with …, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369100023_Sub-mW_Neuromorphic_SNN_Audio_Processing_Applications_with_Rockpool_and_Xylo 22. Edge AI and IoT – Neuromorphica, https://www.neuromorphica.com/applications/edge-ai-iot 23. Neuromorphic Computing for Scientific Applications – OSTI, https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1928928 24. Fundamental Survey on Neuromorphic Based Audio Classification – arXiv, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2502.15056? 25. sensors.ini.ch – Institute of Neuroinformatics, https://sensors.ini.ch/ 26. Tobi Delbruck – Institute Members | Institute of Neuroinformatics | UZH – Universität Zürich, https://www.ini.uzh.ch/en/institute/people?uname=tobi 27. News | Otology and Biomechanics of Hearing – Universität Zürich, https://www.otobm.uzh.ch/en/News.html 28. Foreign body response to silicone in cochlear implant electrodes in the human – PMC, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5500409/ 29. Earpiece that speeds up recovery after a stroke | ETH Zurich, https://ethz.ch/en/news-and-events/eth-news/news/2023/04/earpiece-that-speeds-up-recovery-after-a-stroke.html 30. Neuromorphic Audio–Visual Sensor Fusion on a Sound-Localizing Robot – PMC, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3274764/ 31. Neuromorphic Drone Detection: an Event-RGB Multimodal Approach – arXiv, https://arxiv.org/html/2409.16099v1 32. Neuro-LIFT: A Neuromorphic, LLM-based Interactive Framework for Autonomous Drone FlighT at the Edge – arXiv, https://arxiv.org/html/2501.19259v1 33. SynSense: Neuromorphic Intelligence & Application Solutions, https://www.synsense.ai/ 34. Innatera introduces new neuromorphic microcontroller for sensors – Engineering.com, https://www.engineering.com/innatera-introduces-new-neuromorphic-microcontroller-for-sensors/